BEIRUT, Lebanon / DAMASCUS, Syria – Intense airstrikes continued to rain on the southern suburbs of Beirut, Lebanon, a residential area. The ongoing violence has triggered a mass displacement. As of 3 October, more than 1 million people have been displaced or affected as hostilities escalate, according to officials. Around 541,000 people have fled their homes, over 160,000 seeking refuge in overcrowded collective shelters.

According to UNFPA estimates, some 11,600 pregnant women urgently need access to prenatal healthcare, protection, nutrition, clean water and hygiene services.

Close to 300,000 people have fled into Syria from Lebanon, a figure that includes both Lebanese refugees and Syrian returnees. A majority of those crossing the border into Syria are women and children.

Around 2,800 pregnant women are estimated to have crossed the border, grappling with the anxiety of not only where to find shelter but also concerns over how to ensure continuity of care and where to safely give birth. About 310 are expected to give birth in the next month.

Khawla was one of them.

Pregnant with her fourth child, she was forced to flee Mount Lebanon with her three small children in tow. They crossed the border into Syria earlier this week.

“I felt that I was going into the unknown,” she told UNFPA, the United Nations sexual and reproductive health agency.

It was not her first experience of displacement. She is a Syrian national who had fled war in her own country. Lebanon was her safe haven from violence for three years – but no longer.

“I had to flee to ensure I could give birth in a safe place,” she describes. “I couldn’t imagine delivering my child in the midst of war.”

But that is exactly what happened.

Birth on the border

Khawla’s contractions started while she was en route across the border to Syria, a country still reeling from its own crisis.

“The fear and pressure were overwhelming,” she said. Compounding her anxiety was the fact that her husband had been unable to join them. She was going into labour while caring for her three children alone.

“I feared that I would give birth early. Every step felt like a risk to my baby’s health.”

As her labour pains intensified, the family was made to switch buses. At the stop, she sought help from a mobile medical team from the Syrian Family Planning Association, a UNFPA partner providing essential services at the government border health centre.

They stepped into action. “The team treated me with professionalism and care,” Khawla described. “They placed me in a wheelchair and started the necessary examinations.”

Khawla says her emotions were swirling. “I was giving birth on the border, surrounded by displaced families who shared the same pain and fear,” she said. “But when I heard my daughter’s cry, everything stopped. I felt her warmth, and at that moment, all my fears melted away. I felt stronger than ever.”

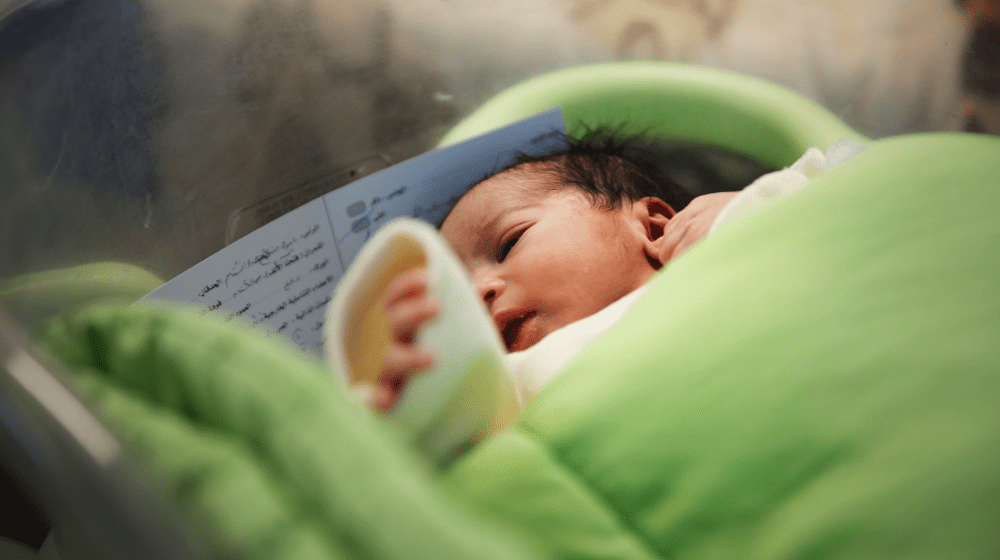

Khawla named her newborn daughter Amal, which means “hope”.

Health system fraying

Khawla was fortunate to find medical support just as she needed it. Too many displaced women and girls – both those streaming into Syria and those seeking shelter within Lebanon – are not so lucky.

At least 73 health workers have been killed, and many more injured, in Lebanon since October 2023. Six hospitals have now been forced to evacuate, and – 40 out of 317 primary health facilities are closed. Even before the current escalation 10 per cent of health centres in Lebanon had shut their doors.

The situation in Syria is similarly bleak: Nearly half of health facilities are partially or completely damaged and there is a chronic shortage of medical equipment and supplies, compounded by limited staffing.

Health officials are urgently trying to fill the gaps left by shuttered health facilities and displaced medical personnel. Hiba Kchour, a UNFPA sexual and reproductive health programme analyst in Lebanon, is one such displaced person. She has been forced to flee within her country twice, first in July and again last week.

“We had to decide which nephew escapes in which car, and with who, in case one of the cars was hit on the way,” she described.

Still, Ms. Kchour has continued to provide support to other affected women and girls. UNFPA is scaling up its support for displaced women and girls, many of whom are crowded into shelters and grappling with hygiene and safety concerns.

“This is the core of our work, and it is our responsibility to respond to women and girls’ escalating needs, especially during emergency situations,” she said.

UNFPA is calling on all parties to the conflict to protect civilians, hospitals, health facilities, medical personnel and patients. “The interruption of essential life-saving health services for women and girls is deeply concerning. The need for protection is urgent. It is a matter of life or death, including for UN staff,” said Laila Baker, UNFPA’s Regional Director for the Arab States Region.

With funding from the European Union, UNFPA is also increasing support to partner groups working in Syria to provide urgent sexual and reproductive health care, prevention of and response to gender-based violence, and psychosocial care for trauma and anxiety. They are also distributing essential medicines, nutrition supplies and dignity kits, which contain essential hygiene items.

As for Khawla, she and Amal were transported to a hospital in Damascus, where they received necessary tests, vaccinations and Amal’s birth certificate. They are now planning to start life anew in Khawla’s hometown.

“We will return to our home in Manbij, in Aleppo.” Khawla says. “It may not be easy, but for Amal’s sake, I want to build a future without fear. I want her to grow up knowing that even in the darkest moments, there is always hope.”