BEIRUT, Lebanon/ DAMASCUS, Syria – More than 11,000 pregnant women have been impacted by the escalated bombardment of Lebanon. Some 1,300 of them are expected to give birth in the next month, even as an estimated one quarter of the country’s infrastructure has been destroyed. The health system, already stretched before the current crisis, has been pushed to the brink – some 100 primary healthcare centres and dispensaries have closed, as have multiple hospitals.

The crisis in Lebanon has “taken on an entirely different nature and scale,” the United Nations Secretary-General said last week, uprooting over a million people, many of whom have crossed the border into also-embattled Syria.

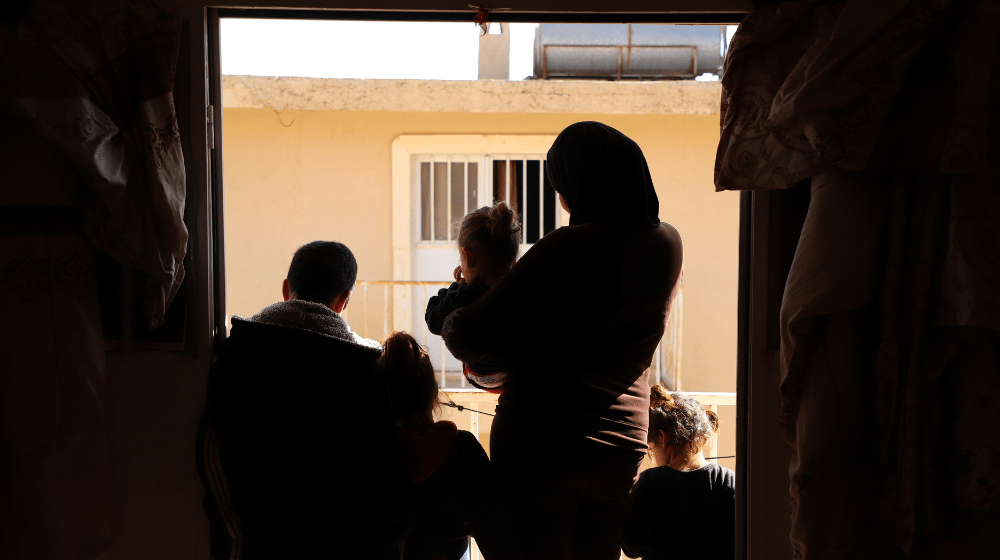

When shelling began in southern Lebanon, "we didn’t know where to go,” Soumaia told UNFPA, the United Nations sexual and reproductive health agency. “We had no family, no friends to turn to.”

She and her husband fled with their eight children – and Soumaia was pregnant at the time. Together, they headed towards Syria, a journey that took four days with little food, only to find the borders closed.

It took days more before they were able to enter the country, then transit to a shelter in Al-Horjelah in rural Damascus.

It was there she experienced a stillbirth: “I woke up in the middle of the night with sharp pain and cramps. When I went to the bathroom, I realized that something was wrong. I was in my fifth month of pregnancy, and my baby was gone."

Soumaia was rushed to the maternity hospital, where doctors were able to remove the placenta and manage her bleeding. "Losing my baby in the midst of all this chaos felt like the final blow," she said.

Displaced again and again

A majority – some 52 percent – of those internally displaced within Lebanon are women and girls. Dania* is among them. She has been forced to relocate three times since the crisis began – twice while pregnant.

The first time, she fled her home in Kfarkila on the southern Lebanese border, in November 2023. She was four months pregnant at the time, and air strikes in their village were escalating. She, her husband and their 4-year-old son moved in with friends in Nabatieh. Later, they moved in with Dania’s relatives, who had also been displaced. In May of 2024, she gave birth to a baby girl, Aya, by Caesarean section, at the Sheikh Raheb Hospital.

“Nabatieh was then attacked in September. We were in survival mode and had to evacuate again immediately, but we had no idea where to go and had already spent all of our savings,” Dania said.

“When the first airstrike hit, it was so close,” she recalled. “My husband had taken my son for a walk outside, and for a few minutes, I thought they were dead. My first instinct was to grab Aya from my sister, as if she was somehow safer in my arms, and run towards the door to find the rest of my family. I didn’t realize I had gone temporarily deaf, and couldn’t hear my mother shouting, ‘They’re right outside the house, you can see them from that window’.”

The family left Nabatieh for Beirut, where they moved into the Basta Middle School, a temporary shelter housing dozens of families.

“We are now sharing a classroom with my husband’s brother and his family of three,” Dania told UNFPA. Baby Aya, now 6 months old, is the youngest person at the shelter – but not for long. Two more shelter residents are pregnant.

Shoring up health services

UNFPA is supporting maternal health services for displaced pregnant women at 30 hospitals across Lebanon. This support includes covering the costs of procedures and providing medicines and supplies for safe deliveries and emergency obstetric care. Supplies, contraceptives, and reproductive health medicines have also been delivered to 70 primary healthcare centers in Akkar, Aley, Chouf, Saida, Sour, Tripoli, and Zahle.

UNFPA is also deploying medical mobile units to shelters throughout the country to conduct needs assessments, provide basic healthcare services, and provide referrals for additional care. Refresher training on emergency obstetric care for staff at government hospitals has also been provided, helping healthcare providers recognize danger signs in pregnancy, identify reproductive health infections and prescribe contraception.

UNFPA is also supporting health and psychosocial services in Syria, including through partners such as the Syrian Family Planning Association.

Soumaia, in Al-Horjelah shelter, received support from the Syrian Family Planning Association after her tragic stillbirth.

"They gave me vitamins and painkillers, as well as a hygiene kit. They also gave medicine and nutrition for my children," Soumaia recalls. "I didn’t even have clothes for myself or my children. But they contacted other organizations and helped secure what we needed."

She also received psychosocial support to address her grief. "The psychologist listened to me. She didn’t rush me or judge me. For the first time since all of this happened, I felt heard."

*Name changed for privacy and protection